This post is also available in:

Indonesian

Indonesian

It was seven o’clock in the morning. Pak Basir’s fishing boat was set to go, his fishing gear laid out on the deck. The sky looked clear with a few light clouds breaking through the blue – ideal for fishing. Pak Basir, a Bajo fisher from Uwedikan Village, was going to try his luck to catch some octopus today.

He steered his boat towards Balean, the best octopus fishing spot in Uwedikan Village. Pak Basir stopped his boat and cleared his SCUBA mask with a mangrove stick, “It can prevent fogging in your mask,” he told me. He put the mask on and leaned over the edge of his boat, immersing his face in the water.

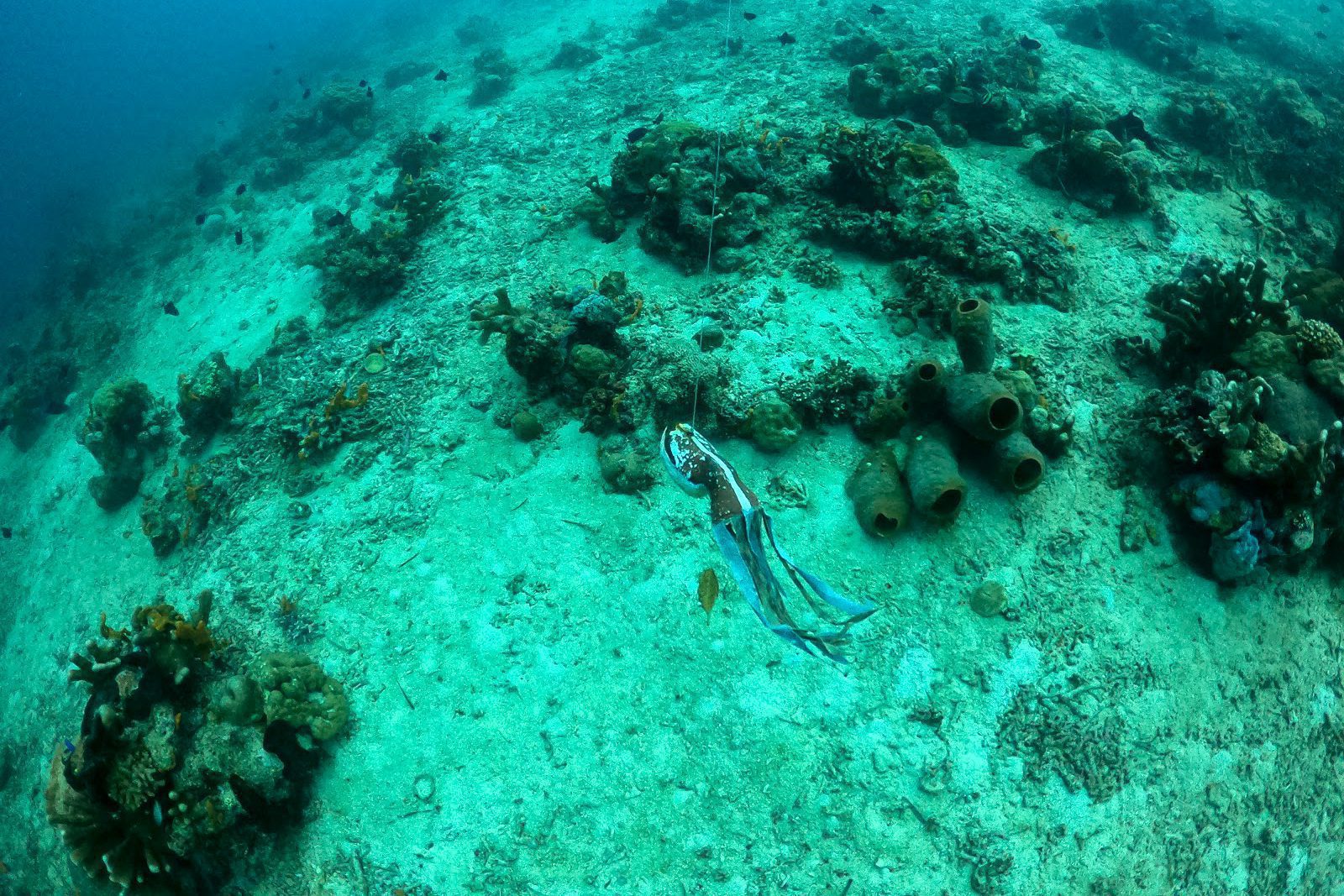

In his left hand, he held a manis-manis (an octopus-shaped bait) and in his right, he used the dayung (ore) to control the movement of the boat. An octopus started to swim toward the manis-manis, revealing its hiding place in the reef. When the octopus began to tire, Pak Basir took a big breath before diving to catch it with his bare hands.

But Pak Basir quickly realised the octopus was too small, so he released it back into the ocean.

A manis-manis is an octopus-shaped bait that fishers use to entice octopus out of the reef | Photo: Rayhan Dudayev

Protecting Uwedikan’s fisheries

Uwedikan is a beautiful coastal village in Central Sulawesi, Indonesia, which attracts local tourists for weekends of camping and snorkeling. Aside from tourism, many of the village’s residents rely on octopus fishing to earn an income. Back in February 2021, I had joined Pak Basir on an early morning fishing trip while visiting the village to support Japesda, one of Blue Ventures’ partner organisations in Indonesia. Japesda are working with the community in Uwedikan, enabling them to lead marine conservation efforts to manage and protect their octopus fishery.

In Saluan (a local language), Uwedikan refers to water and fish (uwe meaning water and dikan meaning fish); fishing is not only the primary source of income for people in Uwedikan, it defines their entire identity as a community,” Marwan, a community member from Uwedikan said to me.

The journey of achieving MPA status began in 2008, as destructive fishing activities, including the use of poison and bombs, were destroying the nearby coral reef ecosystem.In 2019, Uwedikan formally became part of a marine protected area (MPA) legislated through the Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries (MMAF). The journey of achieving MPA status began in 2008, as destructive fishing activities, including the use of poison and bombs, were destroying the nearby coral reef ecosystem.

In 2017, the community in Uwedikan Village, started to lead their own fisheries management efforts by establishing a community-based MPA group, supported by Japesda. The aim of the group is to protect Uwedikan’s coastal resources by monitoring the area to keep it safe from destructive fishing, and to lead other conservation initiatives, such as participatory octopus fishery monitoring.

Collecting octopus data

Since March 2020, the fishers of Uwedikan Village have been monitoring their octopus catch through participatory data collection. This, combined with their existing traditional knowledge of the fishery, helps them to understand its potential and decide how to manage it sustainably.

With terrestrial resources, trees can easily be counted one by one, but marine resources are more difficult to count. For example, the method of octopus fisheries monitoring involves things like recording octopus size and sex,” said Jali, a community organiser from Japesda.

“In the beginning, establishing participatory monitoring in Uwedikan wasn’t smooth sailing, as octopus buyers were concerned that data collection would reduce the quality of the catch,” Indira Moha told me, an octopus data collector from Japesda.

“But, through clear communication and ensuring strict hygiene measures while monitoring the octopus, the buyers allowed the data collectors to monitor the octopus,” she added.

By working closely with the community, Japesda has been able to communicate the benefits of participatory monitoring and now, in Uwedikan Village, octopus fisheries data belongs entirely to the community.

Japesda and the community data collectors have since gained support from the private sector, after presenting the community-led monitoring initiative to one of the biggest fish buyers that trades with Uwedikan village.

Learning through data feedback sessions

After three months of collecting data, fishers in Uwedikan Village take time to analyse the data to gain a deeper understanding of the state of their fishery. After three months of collecting data, fishers in Uwedikan Village take time to analyse the data to gain a deeper understanding of the state of their fishery. This is done through data feedback sessions facilitated by Japesda, which communicate the data in an accessible and culturally relevant way.

In these sessions, the community has the opportunity to see how much they’ve earned from octopus every month, how many kilograms of octopus were caught, and even see who caught the biggest octopus!

During my visit to Uwedikan in February, I had the chance to participate in a data feedback session and observe the community discussing how best to manage their marine resources.

Sparked by Japesda’s colourful data visualisations, the fishers talked about what size octopus they should be catching. They realised that if they catch fewer medium-big sized octopus (<1.5 kilograms) rather than catching lots of small octopus, they can earn more money. They also noted that this is more sustainable too, as it allows smaller octopus to grow and spawn. Now, as Pak Basir demonstrated to me on our early morning fishing trip, fishers in Uwedikan will immediately release an octopus back into the ocean if it’s too small.

“Maybe, we could also close some of the area for a while so the octopus have a chance to regenerate,” Pak Arif, a village officer, raised his voice. As part of a learning exchange with the Darawa community in Wakatobi, Southeast Sulawesi, in December 2020, he had witnessed the successes of a community-led temporary octopus fishery closure and wanted to see if it could have similar results in Uwedikan.

After the session, the community agreed that for now, they will simply continue with participatory monitoring for at least six months. That way, they’ll have a clear trend of data to base future decisions on. In another three months, they will hold another data feedback session, building a bank of knowledge about their marine environment.

Co-management within the MPA

Participatory octopus fishery monitoring is just one example of how this community is getting involved in marine conservation and working in harmony with the MPA. Whilst the MPA is managed by the provincial government, the communities are increasingly involved through co-management and collaboration.

Through these efforts, the community is hopeful that in the near future they will be able to be a key stakeholder in the management of the MPA.In Uwedikan, the community-based MPA group is collaborating with MPA managers by taking on some of their surveillance responsibilities and applying the knowledge they are learning from participatory octopus fisheries monitoring. Through these efforts, the community is hopeful that in the near future they will be able to be a key stakeholder in the management of the MPA.

When MPA managers engage local fishers through co-management, they can not only draw on the knowledge of traditional fishers, but they can also empower coastal communities to grow their profile as fisheries decision makers in their local context. In Uwedikan, that means protecting their local coral reef, which not only entices tourists to the village, but is also home to the rich marine biodiversity that sustains this community and generations to come.

We would be devastated if our house was destroyed. This also applies to coral reefs. We pay for our children to go to school using the fish we catch, so we need to protect their house, the coral reef,” Pak Basir said to me on our last fishing trip together.

By engaging in community conservation and MPA management, the community in Uwedikan can protect their precious coral reef | Photo: Christopel Paino | Japesda

Learn how Japesda are sharing octopus knowledge – virtually!